If you’ve spent much time on the internet recently you might have noticed something: it’s gotten really fast-paced and really fun. It just keeps getting faster and funner. Bitcoin, Clubhouse, NFTs, unicorn startups galore, the Creator Economy. Each feels simultaneously like a potential fad and a nascent revolution.

From the eye of the storm, it’s hard to tell exactly what it means. Will digital artists continue to mint millions from NFTs? Will Creator Economy startups continue to raise early stage rounds at dizzying valuations? Will consumer social apps need top-tier influencer founders to cut through the noise?

I have no idea, and instead of singling out any company or NFT, a thought exercise seems more appropriate, based on three ideas that keep coming to mind:

- A main Not Boring theme that Genies don’t go quietly back into bottles.

- Chris Dixon’s famous line that “the next big thing will start out looking like a toy.”

- Ben Thompson’s idea that media businesses are the first to adapt to new paradigms because of their relative simplicity, and others follow later.

Taken together, what I see happening is this:

The Creator Economy and NFTs are massive human potential unlocks. Even if certain assets are in a short-term bubble, we are on an inexorable march towards individuals mattering more than institutions.

We’re on the precipice of a creative explosion, fueled by putting power, and the ability to generate wealth, in the hands of the people. Armed with powerful technical and financial tools, individuals will be able to launch and scale increasingly complex projects and businesses. Within two decades, we will have multiple trillion-plus dollar publicly traded entities with just one full-time employee, the founder.

That sounds bold, but it’s kind of already happened: as of last week, Bitcoin, which has no employees, crossed the $1 trillion mark.

I think that the Passion Economy broadly will continue to expand beyond media and entertainment and that we’ll see more and more companies -- some small, some big; some permanent, some temporary -- that do all of the things that companies do today, with one person. That doesn’t mean we’ll all be sitting in our basements, alone, growing rich and unhappy; to the contrary, I think we’ll see the continued rise of collectives and communities, some lifelong and some project-specific and fleeting. Some of us might even choose to work together.

Why does it matter that one person will be able to launch companies that rival corporations in scope, scale, and innovation? Because currently, Passion Economy businesses are tied to the creator. Creators, even well-paid ones, are still more labor than capital. If I get hit by a bus tomorrow, the content stops, and Not Boring stops making money. We’re after products can outlive their founders and continue to produce wealth after they’re gone.

People follow people, not companies, but companies have long had the advantage because of all of the coordination it takes to build scaled products. As a result, they capture a disproportionate share of the profits. Even Creator Economy platforms like Substack and TikTok treat creators themselves as commoditized supply. While people are making great livings through their work, which is a great step, I think the confluence of the Passion Economy, DeFi, and NFTs will mean that the creators themselves will capture the lions’ share of the profits. I’m excited to see more individuals commoditize platforms, instead of the other way around.

We haven’t scratched the surface of the implications of giving the power to the person. Today, we’ll scratch.

- Creators’ Crazy Month

- The Creator Toolkit

- Coase and the Nature of the Firm

- The New Nature of the Firm

- The Age of Individual Influence

It’s a great time to be a person.

Creators’ Crazy Month

It’s been quite a year for the Passion Economy. Back in October 2019, pre-COVID, Li Jin wrote The Passion Economy and the Future of Work. In it, Li highlights that “Users can now build audiences at scale and turn their passions into livelihoods, whether that’s playing video games or producing video content.”

Note: We’ll use Passion Economy and Creator Economy interchangeably, but Creator Economy is technically a subset of the Passion Economy that’s more focused on media and entertainment.

The piece was one of those magical self-fulfilling ones that both names a trend and supercharges it. By naming it, Li gave people license to go out and build, both as individual creators and as companies formed to build the tools to grow the movement. COVID helped, too, with more people stuck at home and facing uncertain job prospects. This newsletter is part of the Passion Economy, and it probably wouldn’t exist without COVID.

The Passion Economy just keeps picking up momentum, and it’s reaching a fever pitch. While TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram keep exploding, new entrants are joining the party with breathtaking speed. In the past month alone:

- Clubhouse raised its Series B at a $1 billion valuation and announced plans to let creators monetize directly from the audience through tips, tickets, or subscriptions.

- Creator finance platform Stir raised its Series A at $100 million (a16z led both Clubhouse and Stir).

- Substack announced that there are over 500,000 paid subscriptions on the platform, and that the top ten writers collectively make over $15 million.

- Twitter acquired newsletter platform Revue.

- YouTuber David Dobrik launched his photo app, Dispo, and it went so viral so quickly that it’s in talks to raise at its own $100 million valuation. (Read Divinations on Dispo).

- LinkedIn (LinkedIn!!) is building a service called Marketplaces to compete with Fiverr and Upwork to connect freelancers and hirers.

- Li unveiled her own $13 million early stage venture fund, Atelier Ventures, to invest in the Passion Economy (and instead of announcing in a major publication, she dropped the news in an interview in Lenny’s Newsletter).

That’s just the past month, and the list goes on. Given my intersection as both a creator and an investor, I probably get a pitch for a new Passion Economy company at least once a day. In a little over a year, the Passion Economy has gone from an unnamed je ne sais quoi to one of the hottest early stage investment categories.

Beneath the flashy headlines, regular people are starting to make great livings as part of the Creator Economy, both those who choose to go solo and those who decide to let the market set the price for their talents. The globalization of the talent marketplace means that more people are making more money doing what they do best.

My sister told me that because of global demand from companies that have accepted that remote is here to stay, the salary for top Nigerian engineers has increased by 2-3x in the past month. My friend Dror Poleg would suggest that that’s just the beginning -- he writes about the 10x Class, “a whole new layer of professionals that earn incomes that are a level below the biggest earners in their field, but still much higher than what the average employee could earn in the pre-internet era” because of demand for their niche skill in the global marketplace. He thinks of it as gig workers in reverse -- where the clients are commoditized and the individuals are the secret sauce. Power to the person.

And all of that is just in the mainstream, Web 2.0 Passion Economy. If you expand the definition to include Web3, things get even more insane. On Thursday, digital artist Mad Dog Jonesbroke an NFT record by selling $4 million worth of tokenized animations of his Tokyo artwork in 9 minutes on Nifty Gateway. Thousand-person companies would kill for sales like that.

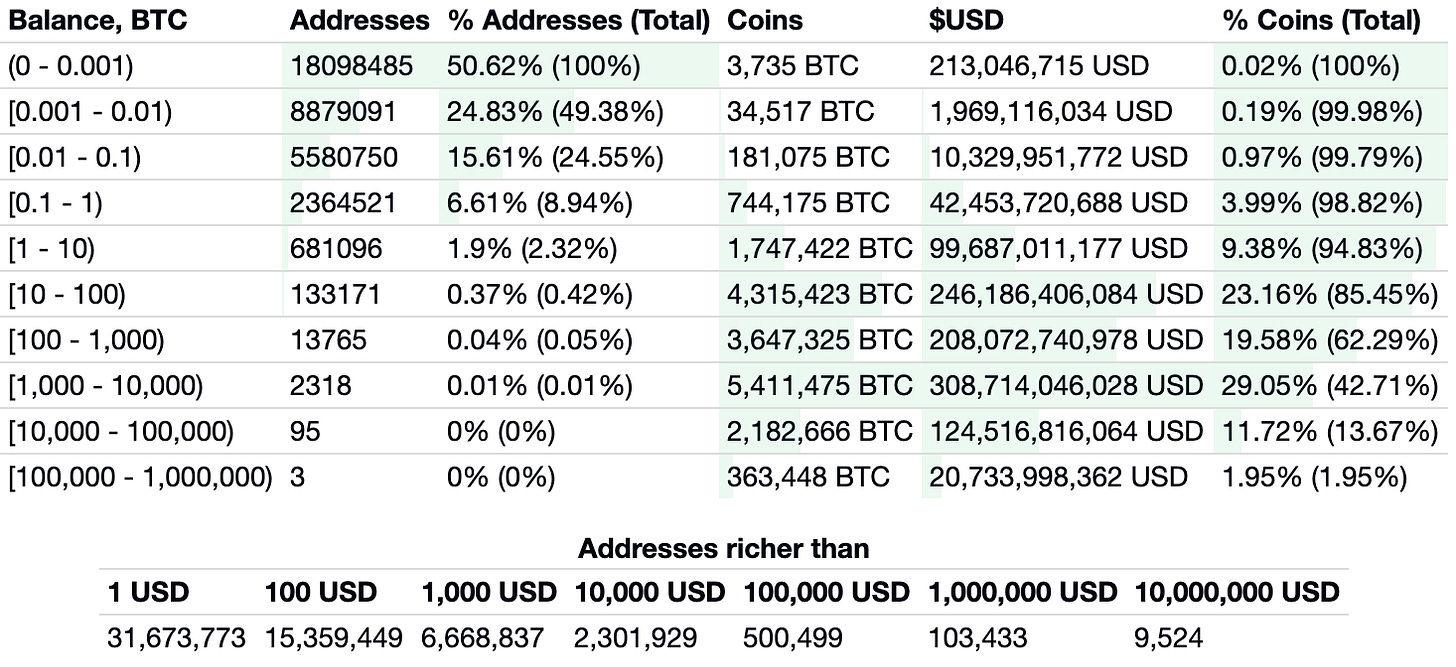

More broadly, the NFT and crypto space has been on an absolute heater. Dapper Labs, the company behind NBA TopShot, which I wrote about in The Value Chain of the Open Metaverse, is rumored to be raising $250 million at a valuation north of $2 billion. Bitcoin broke $50k for the first time on Wednesday, and there are now over 100k addresses that hold over $1 million worth of Bitcoin.

Bitcoin isn’t traditionally grouped with the Passion Economy, but a combination of ownership and fandom has rewarded hundreds of thousands of people with net worths higher than the US median of $121k, and given them career leverage they likely wouldn’t have otherwise had. Power to the person.

It seems crazy out there, bubbly, like 2000 or at least 2017 (the last crypto craze) all over again, and we haven’t even talked about Unisocks yet. These are actual, limited edition socks, backed by the $SOCKS token. The current price is $72,242.77. Or this Non-Fungible Pepe that sold on OpenSea for 110.58 ETH ($216k USD). Or the Logan Paul NFT drop that has generated over $3.4 million in one day.

There are so many more examples. Every time I opened up Twitter this weekend, I saw a new NFT making over $1 million in like an hour. NFTs have gone mainstream, and creators are making bank.

We have YouTube stars launching $100 million photo apps and $3.4 million NFT sales, $2 billion NFT companies, $72k socks, and the world’s largest companies starting to get involved. It’s almost impossible to tell what is real and what is going to blow up. But something is clearly happening.

We are in the early stages of the Creator Economy and NFTs. They look like toys. Currently, the main beneficiaries of the Passion Economy and NFTs are traditional Creators - artists, writers, entertainers. It’s easy to dismiss the confluence of these threads as a COVID-and-Bitocin-induced bubble waiting to pop. But a much bigger shift is underfoot.

The Creator Toolkit

Today, NFTs almost exclusively back digital art and fashion, and the most popular creator tools are focused on media, art, education, and entertainment. Even the ones that go beyond that are too prescriptive to build trillion-plus dollar solo public companies with. But away from the splashy headline numbers, new tools mean new opportunities for millions of people.

Many of the Creator Economy companies that have received the most funding and attention are purpose-built for a specific medium, the Creator Economy equivalent of Vertical SaaS.

- TikTok is for short-form mobile video.

- YouTube is for longer-form video.

- Twitch is for streaming (mainly) video games.

- Instagram is for photos.

- Substack and Revue are for newsletters.

- OnlyFans is for (mainly) adult content.

- Teachable and Wes and Gagan’s Startup are for online courses.

- Clubhouse is for audio conversations.

There are also more horizontal companies that support creation or monetization:

- Descript is for audio and video editing.

- Patreon and Buy Me a Coffee are for subscriptions and tipping.

- Stripe is for payments.

- Stir lets creators manage their finances and collaborations.

- Linktree and Beacons give creators one central home for all of their channels.

Together, these companies focus on helping creators create, grow, manage, and monetize their audiences. That’s incredibly important. As we’ll discuss, solo builders’ main weapon is their ability to build relationships at scale and distribute their products.

But it’s also just the beginning. Ben Thompson has said that media companies are the first to adapt to a new paradigm shift because of the relative simplicity of their products. They require very little coordination among parties, just the ability to capture and distribute one person’s thoughts, images, or dance moves.

Take Not Boring, for example. Starting this business meant signing up for Substack, writing in Google Docs, making (beautiful) graphics in Figma, incorporating with Stripe Atlas, setting up a bank account with Mercury, recording and editing podcasts on Descript, releasing them on Anchor, and being loud on Twitter. That’s it.

It’s a ton of work, but it’s not complex. The same can be said for Addison Rae’s TikTok following or Harry Stebbings’ podcast empire. Obviously, from there, it can get more complex. Addison and Harry both monetize in all sorts of interesting ways. But the basics are simple.

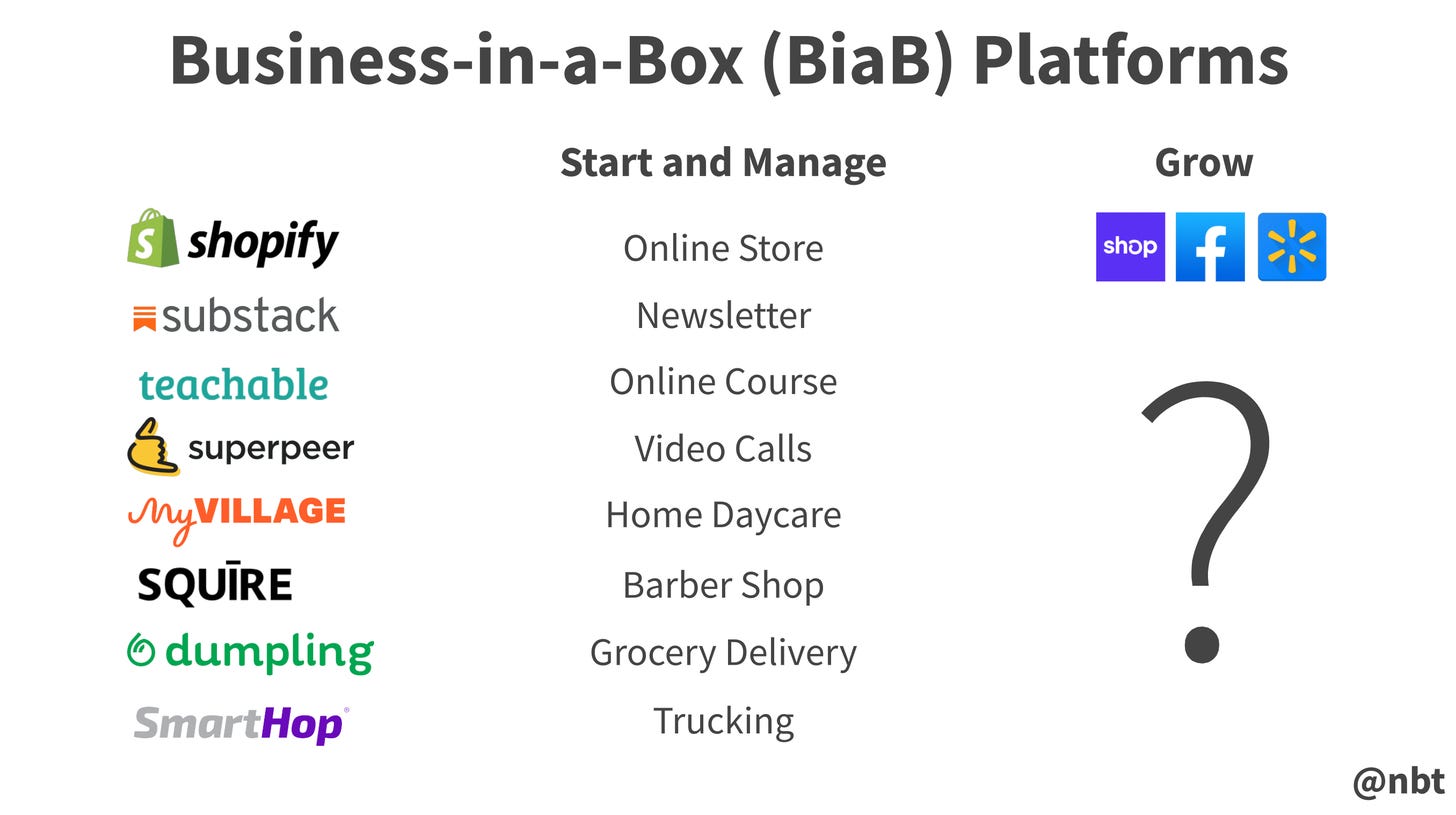

Other Passion Economy companies, which Nikhil Basu Trivedi (NBT) calls Business-in-a-Box (“BiaB”) companies, let people build small businesses beyond media and entertainment. These include some of the media businesses mentioned above, but expand into the physical world with daycare, grocery shopping, and even trucking.

The idea behind these companies is that people don’t need to be gig workers for someone else; they can build their own businesses within a category. Why work for Instacart when you can be your own boss with dumpling?

These businesses offer incredible freedom, ownership, and flexibility to a new class of digital-first small business owners, and many people have used them to create financial independence or even generational wealth for themselves and their families. Teachable founder Ankur Nagpal tweeted that the top 10 creators on Teachable have collectively made over $100 million!

That’s real money, orders of magnitude more than teachers typically make. Individuals are opting out of the traditional path and building something of their own. But for every creator making millions, the platforms on which they operate make billions. That’s fair, that’s how the economy works.

What we’re after in this thought exercise, though, aren’t full-fledged businesses-in-a-box solutions, but a new set of primitives that individuals can mix and match and build on top of to create new products and massive businesses.

We want to see individuals compete with the platforms themselves, create entirely new innovations, and fundamentally alter the nature of the firm.

Coase and the Nature of the Firm

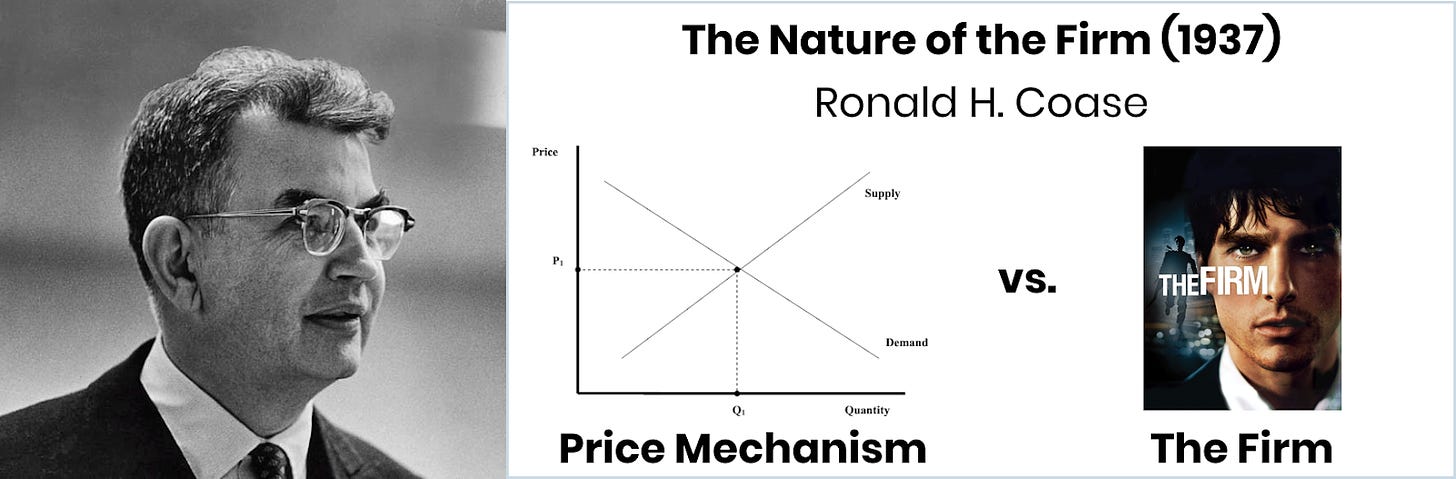

In 1937, economist Ronald Coase wrote a relatively short paper that would ultimately win him the Nobel Prize: The Nature of the Firm. That paper remains fundamental to the way we think about why firms, or companies, exist, when they should or should not, and how big they should be.

In the paper, Coase wrestled with the apparent contradiction between the idea that free markets, or economic systems, should be able to direct resources to the right places without central planning, by using the price mechanism alone. Supply and demand curves and all that. The prevailing economic theory pre-Coase said that because markets are efficient, it should always be cheaper to contract out work than to build a firm. But that was very clearly not happening in practice.

Why then, Coase wondered, do firms exist instead of a multitude of self-employed people who contract with each other on an as-needed basis? What causes an entrepreneur to start hiring people instead of contracting?

Coase uncovered two competing forces: transaction costs lead to the creation of the firm, and overhead and bureaucracy costs limit the firm’s size.

Transaction costs like search and information costs, bargaining costs, and keeping and enforcing trade secrets meant that the cost of obtaining a good or service is higher than just the price. That’s why entrepreneurs hire people: employing a trusted CMO, for example, meant that the entrepreneur didn’t need to start each marketing campaign with a recruiting process, information dumps, and goal-setting, and didn’t need to worry that the marketer would bring all of her company’s information and goals to a competitor at the end of the campaign.

Overhead and bureaucracy costs include wasted organizational time -- think of all of recurring meetings you have on your calendar -- and the propensity for an overwhelmed manager to make mistakes in resource allocation.

Those two sets of costs are in a constant, dynamic tension and determine the ideal size for a firm at a given time. So if we’re thinking through how to get a firm size back down to one, and to let the free market do it’s thing, what we’re looking for is a dramatic decrease in transaction costs, a dramatic increase in overhead and bureaucracy costs, or both combined.

The New Nature of the Firm

The limit to the size of the firm is set where its costs of organizing a transaction become equal to the cost of carrying it out through the market.

-- Ronald Coase

Thanks to new tools and technologies, we are nearing the point at which the costs of carrying out a transaction through the market are getting so low that firms are less necessary.

Recall that Coase highlights three main types of transaction costs: search and information costs, bargaining costs, and keeping and enforcing trade secrets. We are on the verge of driving those costs low enough to let market mechanics rule the day in practice and not just in economics textbooks. There are three main drivers:

- Better Software Primitives

- Cryptographic Stigmergy (lol, I’ll explain) and DeFi

- NFTs

Those three categories are the building blocks of the expanding Solo Corporation Toolkit.

Better Software Primitives

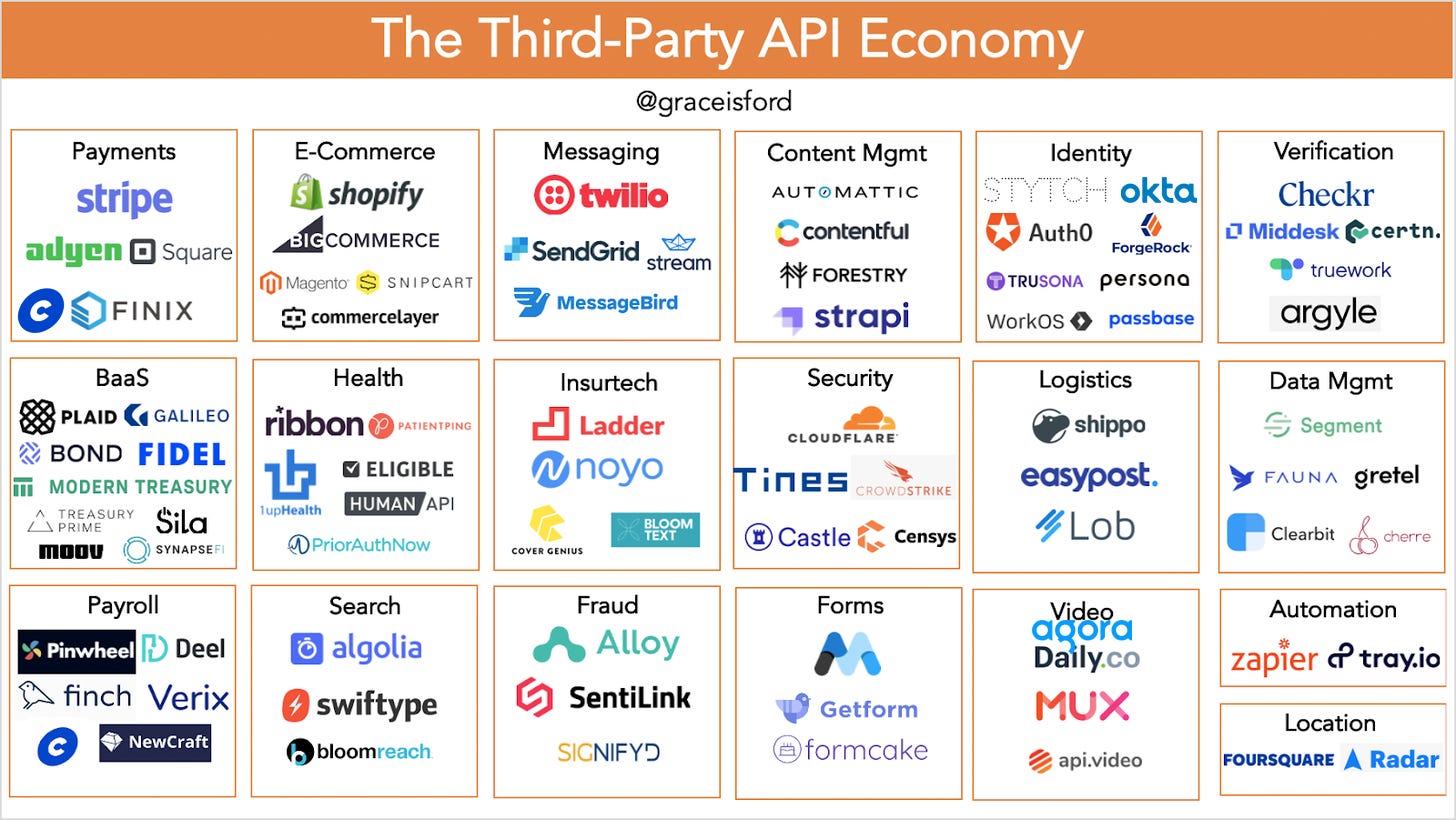

The promise of modern business software is that it allows companies to do more, better, with fewer people than was previously possible. Take API-first businesses, for example. In APIs All the Way Down, I wrote:

When a company chooses to plug in a third-party API, it’s essentially deciding to hire that entire company to handle a whole function within its business. Imagine copying in some code and getting the Collison brothers to run your Finance team.

An increasing number of the things that firms hired whole teams of people to do are now achievable with a few lines of code. This table from Canvas Ventures’ Grace Isford (to which I’ve added a few new ones) captures the breadth of functions now possible via APIs.

APIs dramatically reduce transaction costs. Assuming you have a clear understanding of what you need from an API, that you go with their standard pricing, and that you trust them to keep your data secure, plugging in APIs eliminate each of the categories of transaction costs that Coase highlights.

In addition to APIs, well-funded startups and public companies are building increasingly sophisticated tools with increasingly simple interfaces, making it possible for one person to do in minutes what previously would have taken teams of people months to do. As a stark example, think about the rooms full of typists replaced by a combination of Google Docs or Descript. Copy AI can even write professional quality marketing copy using rough human input.

For less technical people, no-code tools, like Webflow, Zapier, Bubble, Airtable, and countless new entrants enable drag-and-drop building of increasingly complex products. Even large companies with full teams of engineers are beginning to use no-or-low-code tools for certain tasks.

I am dramatically oversimplifying how easy it is to use, let alone combine, all of these tools. It’s taken me weeks to build a website on Webflow, and I still don’t know how to do simple addition in Airtable. We’re not there yet. I’m also skipping huge categories.

My broader point, though, is that while innovation over the past decade has felt stagnant, a lot of work has been done on the building blocks that will allow fewer (and eventually just one) people to build more complex products and businesses with powerful software and machine learning. These primitives will continue to improve, too, and new products will be built that makes it easier to combine and manage all of them, decreasing the overhead and bureaucracy costs of building a company with software.

Instead of AI replacing humans, I’m a big believer that it will give individuals superpowers that let them compete with large companies. As this software becomes more frictionless, the overhead and bureaucracy costs of meetings and management will become more obvious and unnecessary.

At the same time, the blockchain is opening up new possibilities for lowering transaction costs when humans do interact with each other to build something outside the traditional structure of a firm.

Cryptographic Stigmergy and DeFi

In the eighty years since Coase wrote his paper, price and planning have stood as the two ways to organize economic activity. In his paper The Return of ‘The Nature of he Firm’: The Role of the Blockchain, independent scholar Prateek Gohra argues for a third, decidedly less catchy entrant: cryptographic stigmergy. What does that mean?

Stigmergy is the idea that a large group of individuals can interact through identifiable changes in their environment; when that environment is reliably reified in a blockchain, we have cryptographic stigmergy.

Clearer now? No? OK. Gohra is saying that the blockchain offers a third option for organizing economic activity, somewhere between a pure price mechanism and a centrally-planned firm. I summarized further, and then I deleted it, because it’s really dry.

Instead, let’s turn to DeFi + Creators = 🚀 by Tal Shachar and Jonathan Glick, which gets at the same idea in a less “economics paper” way. The two argue that:

By reducing transaction costs, improving information asymmetries and better aligning incentives, decentralized finance (DeFi) will unlock the creator economy. In turn, popular creators and social influencers will push crypto deeper into the mainstream. The effects of this combination will be far-reaching and unpredictable.

The essay focuses on the idea that any product launch that doesn’t include influencers is likely to fail, but that cash and equity don’t properly align the incentives between influencers and companies. Introducing DeFi, they argue, will properly reward creators and influencers for the value that they provide to a project. That’s an interesting idea, but it relies on the limited definition of Creator that we use today. Where it gets really compelling is when they say:

As the market for creators grows, many workers might become more like project nomads than full-time employees. Swarms of talent, community and capital already flock from project to project, and this has been true about open source for decades. Perhaps over time, as these projects become better funded and proven successful, the corporate world itself will be ‘eaten’ or at least transformed by this capital-charged collab culture. Companies and projects might become more like clouds, larger than ever before but with vaguer outlines, eroding the boundaries between employees, consultants, customers and investors.

DeFi, through cryptographic stigmergy, allows talent and contributors to flow as easily from project-to-project as money does today. This is part of the idea behind Fairmint, which Sari Azout and I wrote about in November. Better align financial incentives, and you can attract the right people to your project at the right time. This reduces transaction costs and lets project leaders and workers get market price, and is an important step on the path towards the Solo Corporation, one with just one full-time employee orbited by a constellation of people and tools that float in and out as needed.

If DeFi and cryptographic stigmergy are the forces that allow Creators to snap people and capital into place when needed, lowering search, information, and bargaining costs, then NFTs are the ones that handle trade secrets, and allow Creators to share and remix IP seamlessly.

NFTs

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are cryptographic tokens that prove authenticity, ownership, and scarcity of digital assets.

If you want to go deeper down the rabbit hole, you should check out The Value Chain of the Open Metaverse, which I wrote in January, or Jesse Walden’s NFTs Make the Internet Ownable.

They are the ultimate manifestation of “the next big thing will start out looking like a toy.” The NFT projects attracting the most attention currently really do look like digital toys. NBA TopShot lets people own highlights of NBA games. Logan Paul is giving away Pokemon cards. @optimist is taking over my twitter feed with what can best be described as a gif of cabbage. Beeple’s multi-million dollar digital art collection features a disturbing number of illustrations of a naked Donald Trump.

While provable ownership of digital art and fashion is a total game changer in its own right, and should have huge implications for the Metaverse, this first application masks a ton of powerful applications beyond the worlds of art and entertainment. NFTs and smart contracts have the potential to change the way that we manage Intellectual Property (“IP”).

In The Value Chain of the Open Metaverse, I wrote about a digital fashion company called DIGITALAX that “is based on a parent-child structure, in which the Parent NFT - the final piece - is composed of child NFTs representing all of the materials, patterns, and colors that go into the construction of the garment.” The NFTs that are all over your Twitter feed today are based on the ERC721 asset standard -- one token for one final item -- but DIGITALAX also uses the ERC1155 standard, used for semi-fungible tokens that represent a category of things without concern for exactly which one is used. In DIGITALAX’s case, a final digital dress might be backed by an ERC721 token, but different color patterns or materials would be backed by ERC1155 tokens, which would reward their creators every time the pattern or material is used.

This same concept could be applied to all sorts of things for which we rely on the blunt instrument of intellectual property law today, giving digital assets’ original creators financial upside whenever their work is used instead of the right to sue, and giving new creators the ability to use a wider range of off-the-shelf inputs in their products.

Here are a few concrete examples:

- Music. ERC721-backed songs made up of ERC1155-backed choruses, verses, beats, and hooks, which can be used to make literal remixes that reward the original creators automatically.

- Research. Today, the success of a research paper is measured by the number and quality of citations. What if, instead, the research paper was backed by an NFT that made it free to use for other academic research, but that paid the researcher out any time it was used for commercial purposes.

- Code. Instead of pure open source code, what if code blocks were backed by NFTs that allowed remixing and improvement, but paid out the code’s original author whenever it was used in new, commercial code.

- Stock Images. Photos or illustrations used in website design or marketing materials could pay the original creator.

The possibilities are endless, but making IP more flexible and remixable unleashes benefits far beyond owning a clip of your favorite NBA star’s best dunk. NFTs can help build the Creator Economy’s Middle Class by rewarding original creators every time their work is used, freeing their earning power from labor, and can lower transaction costs for Solo Corporations who want to freely use the best inputs available to build trillion-plus dollar public companies.

Taken together, better software primitives, cryptographic stigmergy and DeFi, and NFTs have the ability to completely redefine and expand what being a Creator means. But no matter which definition you’re using -- from YouTube star to newsletter writer to Creator Jeff Bezos -- the one thing that remains crucially important is the influence of the individual.

The Age of Individual Influence

The reason that the Creator Economy is a thing in the first place is simple: people like people. Over the weekend, I had one of my most viral tweets ever:

It sounds like a high kid thing to say, but it gets at a larger point, which Rodrigo Sanchez-Rios pointed out in the replies: “People follow people, not companies.”

At the same price and quality, we would much rather buy a loaf of bread from the baker next door than from the multinational conglomerate. We’d (I hope!) rather get business analysis from our favorite Substack writer than from an article by a faceless person in Harvard Business Review. We support companies whose CEOs we know, trust, and are inspired by more than those led by faceless and generic professional CEOs.

In Business is the New Sports, all the way back in June, I wrote, “CEOs’ direct connections with fans humanize them and their businesses in a way that wasn’t possible before. It makes us more likely to root for them.” Since then, Elon Musk has memed himself into the richest person in the world by building a ravenously loyal base of Elon Musk, and by extension, Tesla, supporters.

The only thing better than rooting for companies whose CEOs we admire is rooting for individuals who are themselves the company. In DeFi + Creators = 🚀, Shachar and Glick put it well:

Like creator fandom today, every ‘company’ or project will become more like a tribe, driven and defined by the stories and symbols linking its members together, led by those who best weave its narrative.

In a world of abundance, we want to follow the people we trust. The Creator Economy to date has unleashed a wave of people who are world-class storytellers, authentic, and relatable. The next step is for us to not just turn to these people for entertainment and education, but for an ever-larger number of things that we want to accomplish and achieve.

As the costs to launch full-scale businesses come down, supported by new software and crypto tools, individuals with influence will amass increasing power.

Today, this is happening across Substack, TikTok, YouTube, podcasts, Twitter, Teachable, Twitch, Clubhouse, and a growing number of Creator Economy platforms. It’s already beginning to happen in finance, too.

NBT wrote about this idea in The Rise of the Solo Capitalists in July. Instead of working for large VC funds, individuals like Lachy Groom, Josh Buckley, Elad Gil, Shana Fisher, and now Li Jin, are raising their own funds, backed by their own identities, and beating out established funds to win some of the most competitive deals in venture. Everyone read Elad Gil’s High Growth Handbook or Li’s pieces on the Passion Economy, and they want to have those people, not some company with a faceless blog, on their cap table. The Not Boring Syndicate is a (very small) testament to the fact that companies want to work with people who can help tell their stories.

The same transformation is happening to public markets investing, as well. SPACs are a manifestation of the idea that individual sponsors hold as much sway as investment banks. Public and CommonStock allow people to follow other people whose investing acumen they trust, and Composer (NB portfolio company) is going to take that a step further, by making it easy to subscribe to your favorite individual investors’ strategies.

Across media, entertainment, education, ecommerce, and now finance, the power is shifting to individuals. One person, backed by improving tools and their own personal influence, can genuinely compete with established institutions for eyeballs and dollars. Converting individual influence and existing social channels into sales gives Solo Corporations a huge advantage in customer acquisition, particularly when trusted creators form collectives and experiment with new ways of sharing upside with each other and with supporters.

While the idea of a trillion-dollar public Solo Corporation seems crazy from where we sit today, it’s inevitable. Genies don’t go back in bottles. And although the Creator Economy and NFTs seem innocuous and unthreatening to established companies today, they portend the next big thing. It may happen in the next decade, it may take until 2071, but it’s the way the world is heading.

All of that said, just because it will be possible doesn’t mean that everybody is going to go start Solo Corporations.

For one, it’s really hard. In The Innovators, Walter Isaacson is adamant about the fact that throughout history, many people have tried to innovate alone and failed. I’m personally a huge believer in Scenius, the idea that the right groups in the right places at the right times are the ones that create world-changing innovation. Certainly, stigmergy and community can solve some of this; the crypto community is strong, and many within it are like teammates, even if none of them are employed by a company or co-founders.

Plus, working with the right team, when everything is humming, is incredibly fun, and co-founders that complement each others’ skillsets are a powerful force. There’s a reason that Y Combinator strongly prefers companies with co-founders.

Most likely, we’ll see a trillion-plus dollar public company with two-or-three full time partners before we see the public Solo Corporation. A team comprised of a technical genius, a brilliant designer, and a master storyteller would be a hard thing to beat. Maybe that’s the magic of Dispo.

But whether very small teams with enormous impacts, or genuine Solo Corporations, the important thing is that the choice will be ours.

Power to the person.

Thanks to Dror, Ben, and Dan for editing!

Thanks for reading, and see you on Thursday,

Packy